Stages of passing a kidney stone can be a truly harrowing experience. This detailed guide delves into the various phases, from the initial agonizing pain to the eventual elimination and recovery. We’ll explore the different types of kidney stones, their formation, and the specific symptoms associated with each stage. Understanding these stages can help you better navigate this challenging journey and prepare yourself for what’s to come.

From the initial sharp pains to the gradual progression, the body’s response to a kidney stone is complex. We’ll cover the pain patterns, location, and intensity changes. This information will help you understand your experience and know what to expect at each step. We will also cover dietary considerations and medical interventions to help manage and prevent future occurrences.

Introduction to Kidney Stones

Kidney stones, also known as nephrolithiasis, are hard deposits that form within the kidneys. These deposits are typically composed of minerals and salts, and their formation can be influenced by various factors, including diet, genetics, and underlying medical conditions. The prevalence of kidney stones is increasing globally, impacting people of different ages and backgrounds. Understanding the causes, types, and symptoms of kidney stones is crucial for early detection and effective treatment.Kidney stones can vary significantly in size and composition.

Kidney stones can be a real pain, and understanding the different stages of passing them can help you prepare. It’s often a gradual process, starting with mild discomfort that can escalate quickly. Interestingly, some of the early signs of discomfort can mirror other conditions, and sometimes signs like those seen in signs of autism in girls might be mistaken for something else.

Fortunately, as the stone moves through the urinary tract, the pain typically intensifies and then subsides as it’s eventually expelled. Each person’s experience is unique, but knowing the common stages can help you manage the discomfort.

This variability in characteristics leads to a range of symptoms and treatment approaches. The different types of stones require distinct strategies for prevention and management. Identifying the type of stone is essential for tailoring treatment and preventive measures.

Kidney Stone Formation

Kidney stones typically form when the concentration of certain substances in the urine, such as calcium, oxalate, and uric acid, becomes too high. This can lead to the crystallization of these substances, which then clump together to form a stone. Dehydration, a diet rich in certain foods, and certain medical conditions can contribute to the increased concentration of these substances.

Navigating the different stages of kidney stone passage can be tricky, and the pain levels can vary wildly. While dealing with the discomfort, some men might consider options like estrogen blockers for men, a subject worth exploring , but ultimately, the key to managing the process is understanding the specific stages and how your body is reacting. Each stage presents its own unique set of symptoms and potential challenges, so staying informed is crucial for managing the experience.

Types of Kidney Stones

Kidney stones are categorized based on their chemical composition. The most common types include:

- Calcium Oxalate Stones: These are the most prevalent type, often forming when calcium and oxalate combine in the urine. Dietary factors, such as high oxalate intake from foods like spinach and nuts, and insufficient fluid intake, are often contributing factors. Individuals with certain metabolic disorders, such as hypercalciuria (excess calcium in the urine), may also be at a higher risk.

For instance, a diet high in processed foods and low in fruits and vegetables can lead to an increase in urinary oxalate levels, increasing the risk of calcium oxalate stones.

- Calcium Phosphate Stones: Another type of calcium stone, these are less common than calcium oxalate stones. They often form in alkaline urine and can be associated with metabolic conditions or certain medications.

- Uric Acid Stones: These stones form when the urine contains an excessive amount of uric acid. Conditions like gout, a metabolic disorder characterized by elevated uric acid levels, are frequently linked to uric acid stone formation. Also, a diet rich in purine-containing foods (e.g., red meat, seafood) can contribute to this issue. For example, someone with a diet predominantly composed of red meat and organ meats might experience an increased risk of uric acid stones.

- Struvite Stones: These stones are associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs). Bacteria in the urine can produce ammonia, which promotes the formation of struvite stones. Frequent UTIs and certain antibiotic treatments can contribute to their formation. For example, a patient with recurrent UTIs and a history of antibiotic use might develop struvite stones.

- Cystine Stones: These rare stones form due to a genetic disorder that affects the body’s ability to reabsorb cystine in the kidneys. This leads to an excessive amount of cystine in the urine, causing crystallization and stone formation. For instance, individuals with cystinuria are at higher risk of cystine stone formation, requiring specialized dietary and medical interventions.

Symptoms of Kidney Stones

Kidney stones can cause a range of symptoms, depending on their size, location, and composition. Common symptoms include severe, intermittent flank pain (pain in the side and back), often radiating to the groin. Nausea, vomiting, and blood in the urine (hematuria) are also possible symptoms. Pain intensity can vary significantly, but is often described as sharp and excruciating.

For example, the pain can be debilitating, interfering with daily activities and requiring immediate medical attention.

Kidney Stone Characteristics Table

| Stone Type | Formation | Symptoms | Treatment Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Oxalate | High urinary oxalate or calcium levels, insufficient fluid intake, diet high in oxalate-rich foods | Severe flank pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria | Pain management, hydration, medications to dissolve stones, or surgical removal (lithotripsy) |

| Calcium Phosphate | Alkaline urine, metabolic conditions, medications | Similar to calcium oxalate stones, but can also present with urinary tract infections (UTIs) | Dietary modifications, medications to adjust urine pH, surgical intervention if needed |

| Uric Acid | High uric acid levels in urine, diet high in purines, gout | Flank pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, frequent urination, possible pain radiating to the genitals | Medications to lower uric acid levels, dietary changes, hydration |

| Struvite | Urinary tract infections (UTIs) | Severe flank pain, urinary frequency, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting | Treating the infection, surgical removal of stones, possible antibiotic therapy |

| Cystine | Genetic disorder affecting cystine reabsorption in kidneys | Recurring kidney stones, flank pain, hematuria | Specialized dietary interventions, medications to increase urine pH, possibly surgical removal |

Initial Stages of Pain

The initial stages of kidney stone passage are often characterized by intense, sharp pain that can quickly escalate. Understanding the patterns and locations of this pain can help individuals recognize the potential presence of a kidney stone and seek prompt medical attention. This pain, while often debilitating, is a crucial indicator that a stone is moving and requires monitoring.Kidney stones can manifest in various ways, with the initial pain being a significant symptom.

The pain’s intensity and location can vary considerably based on factors like the stone’s size, shape, and location within the urinary tract. Recognizing these variations is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Common Pain Patterns

The pain associated with kidney stones often begins in the back, typically in the flank region (the area between the ribs and hips). This initial pain is frequently described as a sharp, cramping, or throbbing sensation. The pain can radiate to the groin, testicles in men, or the labia in women, as the stone moves along the urinary tract.

Location and Intensity of Pain

The location of the pain is often the first clue to where the stone is situated. A stone lodged high in the kidney may cause pain primarily in the back, while a stone in the ureter, the tube connecting the kidney to the bladder, might produce pain that moves lower, potentially radiating to the groin. The intensity of the pain is directly correlated to the stone’s size and the level of obstruction it creates.

Smaller stones might cause mild discomfort, while larger stones can trigger severe, incapacitating pain.

Kidney stones can be a real pain, and the journey through the different stages can vary wildly. From the initial sharp twinges to the eventual passage, each stage has its own set of challenges. Interestingly, prolonged sitting, a common occurrence in modern life, can increase the risk of kidney stones forming, and also make the experience more unpleasant.

If you’re prone to kidney stones, paying attention to the risks of sitting too long might be a good idea. Ultimately, the goal is to pass the stone as quickly and comfortably as possible.

Variations in Pain Based on Stone Size and Location

A small stone may cause intermittent, mild pain, while a larger stone can lead to continuous, intense pain. A stone lodged near the opening of the ureter, for example, might cause severe pain that is localized and sharp, whereas a stone further down the ureter may result in a more intermittent or throbbing pain that radiates to the lower abdomen and groin.

The stone’s shape also plays a role. A jagged stone might cause more intense pain as it irritates the lining of the urinary tract.

Table Comparing Pain Levels and Locations

| Stone Position | Pain Location | Pain Intensity (Mild/Moderate/Severe) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Flank, back | Moderate to Severe | Sharp, cramping, constant, potentially radiating to the lower abdomen |

| Ureter (upper portion) | Flank, lower back, upper abdomen | Moderate to Severe | Sharp, intermittent, possibly radiating to the groin |

| Ureter (middle portion) | Lower back, groin, inner thigh | Moderate to Severe | Intermittent, throbbing, potentially radiating to the testicles in men or labia in women |

| Ureter (lower portion) | Groin, lower abdomen, genitals | Moderate to Severe | Sharp, intense, radiating to the genitals, potentially causing nausea |

| Bladder | Lower abdomen, bladder area | Mild to Moderate | Pressure, burning sensation, possible urgency to urinate |

The Progression of Passage

Kidney stones, those pesky mineral deposits, don’t just sit there quietly. Their journey through the urinary tract is a complex process, often accompanied by significant discomfort. Understanding this progression is crucial for patients and healthcare providers alike to anticipate and manage the symptoms effectively.

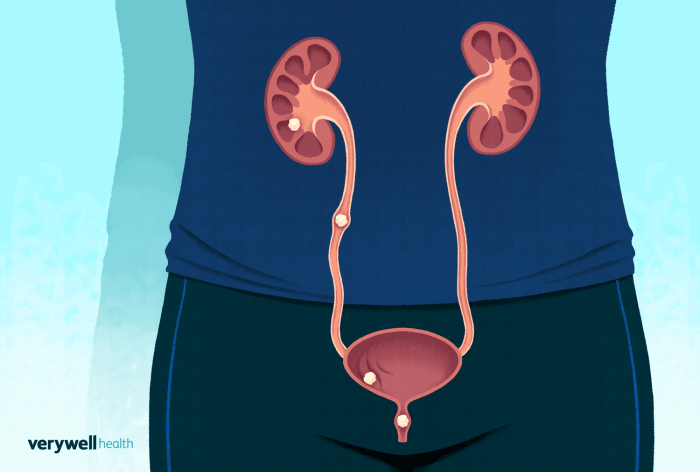

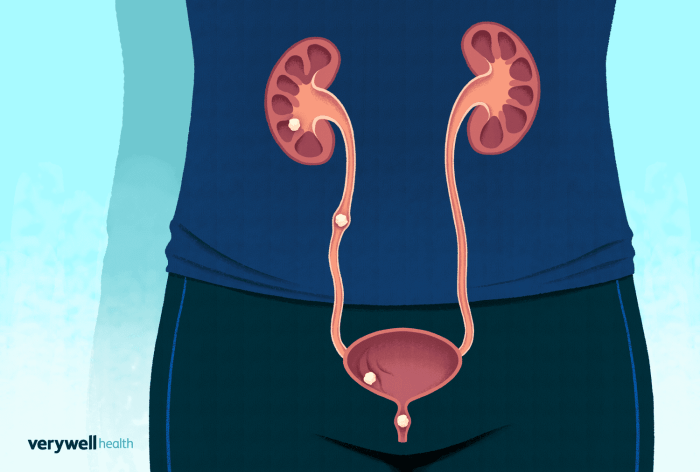

Typical Pathway Through the Urinary Tract

The path a kidney stone takes through the urinary system is generally predictable. Stones typically originate in the kidney, a vital part of the urinary system responsible for filtering waste products from the blood. From there, they can travel down the ureter, the tube connecting the kidney to the bladder. This journey isn’t always smooth sailing, and the body responds in various ways to the presence of this foreign object.

Body’s Response to Stone Movement

The body’s response to a moving kidney stone is multifaceted and often intense. Muscle contractions in the ureter, known as peristalsis, are designed to propel urine down the tract. However, when a stone obstructs the ureter, these contractions become more forceful and spasmodic, trying to push the stone along. This intense muscular activity is the primary source of the intense pain often associated with kidney stones.

Common Symptoms Experienced During Passage

The symptoms a patient experiences during the passage of a kidney stone can vary in intensity and duration, but some common themes emerge. Severe, cramping pain is often described as originating in the flank or side of the abdomen, radiating to the groin or lower abdomen. Nausea and vomiting are also common reactions to the pain. Other potential symptoms include frequent urination, a persistent urge to urinate, and blood in the urine.

The presence of blood in the urine is often a sign that the stone is causing damage to the urinary tract lining.

Flowchart of Kidney Stone Movement, Stages of passing a kidney stone

A simplified illustration of a kidney stone’s journey can be depicted as follows:

Kidney

|

V

Ureter (upper section) ----> Ureter (middle section) -----> Ureter (lower section)

| |

V V

(Possible stone lodgement) Bladder

| |

V V

(Further movement to bladder) Urination

This flowchart highlights the basic stages of stone movement.

It’s important to remember that the exact path and time frame can vary significantly from person to person. Some stones may get lodged in different parts of the ureter, causing prolonged pain and requiring intervention. The journey through the urinary tract can be significantly impacted by the stone’s size, shape, and composition.

Mid-Passage Symptoms

The journey of a kidney stone through the urinary tract is often fraught with discomfort. While the initial pain signals the stone’s presence, the mid-passage phase introduces a new set of symptoms, often more intense and varied than the initial stages. Understanding these symptoms is crucial for patients and healthcare providers to manage the pain and ensure proper treatment.

Common Symptoms During Mid-Passage

The mid-passage stage is characterized by a shift in the location and intensity of pain. The stone, now further along its journey, may be pressing against different areas of the urinary tract, resulting in varying levels of discomfort. This phase often involves a combination of symptoms, some of which are similar to the initial stages, while others are unique to this period.

Comparing Initial and Mid-Passage Symptoms

The initial stages of stone passage are typically marked by sharp, localized pain in the flank or back. This pain is often intermittent and less intense in the mid-passage. As the stone progresses, the pain may radiate to the groin, testicles in males, or lower abdomen in females. The frequency and duration of pain episodes can also fluctuate.

The initial pain tends to be more severe and sudden, while mid-passage pain is often more intermittent and cramping. Furthermore, nausea and vomiting, while possible in the initial phase, often become more pronounced in the mid-passage.

Role of Nausea, Vomiting, and Gastrointestinal Issues

Nausea and vomiting are common complaints during the mid-passage. The pressure and irritation caused by the stone’s movement can stimulate the nervous system, leading to these gastrointestinal issues. Furthermore, pain signals can trigger the vomiting reflex. Other gastrointestinal symptoms like cramping, bloating, and diarrhea can also occur. The severity of these symptoms can vary significantly between individuals.

A person might experience mild nausea, while another might suffer from severe vomiting episodes, making this aspect of the experience challenging to predict.

Symptoms Experienced in Mid-Passage

| Symptom | Description |

|---|---|

| Pain | Intense, cramping, and intermittent. May radiate to the groin, testicles, or lower abdomen. Often less severe than initial pain but more frequent. |

| Nausea | Feeling of unease in the stomach, often leading to vomiting. |

| Vomiting | Expulsion of stomach contents. May be associated with pain and nausea. |

| Gastrointestinal Cramps | Muscle contractions in the stomach and intestines, causing pain and discomfort. |

| Diarrhea | Frequent bowel movements with loose stools. |

| Urinary Frequency | Increased need to urinate, sometimes with pain. |

| Blood in Urine | Presence of blood in the urine, a sign of possible stone abrasion or irritation. |

| Chills and Fever | Symptoms potentially indicating infection, particularly if accompanied by other symptoms. |

Approaching the Exit

The journey of a kidney stone through the urinary tract is often a painful one. As the stone progresses, the intensity and location of the pain can shift, offering clues about its position and impending exit. Understanding these changes is crucial for managing the experience and ensuring a timely resolution.

The final stages of passage often bring a shift in the pain’s character. The pain may become less intense and more localized as the stone approaches the bladder’s opening. This is a positive sign, indicating the stone is moving toward its eventual exit.

Symptoms Signaling Stone’s Approach to Exit

The symptoms experienced as the stone moves closer to the bladder’s opening vary from person to person. However, certain patterns are frequently observed. These patterns include a reduction in the overall intensity of the pain, a change in the pain’s location, and an increase in the frequency of urination.

Changes in Pain Intensity and Location

Pain often shifts from a sharp, cramping sensation in the flank or lower abdomen to a duller ache in the lower abdomen or groin area. This shift is a clear indication that the stone is descending and getting closer to the bladder. The pain may be less intense but more persistent as the stone navigates the narrower passages. The patient may experience less overall pain but more frequent, short episodes.

Potential Complications as Stone Approaches Bladder

As the stone nears the bladder, there is a risk of infection. The urinary tract is a delicate system, and any obstruction can disrupt the normal flow of urine, potentially leading to bacterial growth. A stone lodged in the ureter can also cause severe bladder spasms, leading to frequent and urgent urination.

Signs and Symptoms as Stone Approaches Bladder

| Stage | Symptoms | Pain Intensity | Pain Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approaching Exit | Decreased overall pain intensity, more localized pain in lower abdomen/groin, frequent urination | Moderate to mild | Lower abdomen, groin, or pubic area |

| Stone in Bladder | Increased frequency of urination, urgency, potential discomfort or pressure in bladder, possible blood in urine | Mild to negligible | Lower abdomen, bladder area, lower back (less frequent) |

The table above provides a general overview of the symptoms as the stone approaches the bladder. It’s important to note that individual experiences may differ. Consult a healthcare professional for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Stone Elimination

Kidney stones, once formed, require a path to exit the body. This process, while often natural, can be painful and sometimes necessitates medical intervention. Understanding the various elimination methods and their associated recovery times is crucial for managing the experience and ensuring a smooth recovery.

The success of stone elimination depends on several factors, including the size, shape, and location of the stone. Natural passage, often the preferred method, is not always possible or successful. Medical interventions are available when natural passage is unlikely or proves unsuccessful. Choosing the appropriate approach involves a careful evaluation by a healthcare professional.

Methods of Stone Elimination

Natural passage is the body’s own method of removing stones. This process, while often the first line of treatment, can be challenging and protracted. Factors like stone size and location play a significant role in its success.

- Natural Passage: This involves the stone passing through the urinary tract on its own. This method is often successful for smaller stones, typically under 5mm. Larger stones may require medical interventions to facilitate their passage.

- Medical Interventions: These interventions are employed when natural passage is deemed unlikely or when complications arise. Common medical interventions include lithotripsy and surgical removal.

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL): This non-invasive procedure uses shock waves to break the stone into smaller fragments, making them easier to pass. Success rates are generally high for stones amenable to this method.

- Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy: A thin, flexible tube with a camera and light source (ureteroscopes) is inserted through the urethra and into the ureter to locate and break up the stone. This procedure is often employed for stones in the ureter.

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: This surgical procedure involves creating a small incision in the back to access and remove large or complex stones lodged in the kidney. It is often reserved for stones that are too large or complex for other procedures.

Success Rates and Recovery Time

The success rate of each method varies. Natural passage, while often the first approach, has a success rate that is not consistent across all patients. Medical interventions typically have higher success rates but can also carry risks.

| Method | Success Rate (Approximate) | Recovery Time (Approximate) | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Passage | 50-70% (for smaller stones) | Days to weeks | Non-invasive, minimal risk | Longer recovery time, potential for pain and complications |

| ESWL | 70-90% | Days to weeks | Non-invasive, less invasive than surgery | Possible discomfort, risk of complications (e.g., bleeding) |

| Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy | 80-95% | Days to weeks | Less invasive than percutaneous nephrolithotomy | Risk of bleeding, infection, or injury to surrounding tissues |

| Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy | 90-95% | Weeks to months | Effective for large or complex stones | Higher risk of complications, longer recovery time |

Supportive Care Strategies

Effective supportive care strategies can significantly enhance the stone elimination process and minimize discomfort.

- Hydration: Drinking plenty of fluids helps to flush the urinary tract and aid in stone passage. Aim for at least 8 glasses of water a day.

- Pain Management: Over-the-counter pain relievers can help manage discomfort. However, follow the dosage instructions carefully.

- Dietary Adjustments: Dietary modifications might be needed to prevent future stones. Consult a nutritionist for personalized recommendations.

- Stress Management: Stress can worsen pain. Employing relaxation techniques like meditation or deep breathing can help alleviate discomfort.

Post-Passage Recovery

The journey through kidney stone passage isn’t over once the stone is eliminated. A period of recovery follows, often marked by a gradual return to normalcy. Understanding the typical recovery timeline and the importance of follow-up care is crucial for managing potential complications and preventing future occurrences. This phase focuses on healing, monitoring, and long-term preventative strategies.

Typical Recovery Period

The recovery period after a kidney stone passage varies depending on individual factors, such as the size and location of the stone, and overall health. Most individuals experience a significant decrease in pain within a few days of stone expulsion. Discomfort may persist for a few weeks, but it typically diminishes over time. Rest and hydration remain key components of the healing process during this time.

Importance of Follow-Up Care

Regular follow-up appointments are essential after passing a kidney stone. These appointments allow your doctor to assess your recovery, identify any potential complications, and develop a personalized strategy for preventing future stones. Follow-up care includes monitoring kidney function, evaluating the presence of any residual stone fragments, and exploring potential underlying causes. This proactive approach is critical in preventing recurrent stone formation.

Long-Term Implications of Kidney Stone Occurrences

Kidney stones are not always a one-time event. A history of kidney stones significantly increases the risk of recurrence. Factors such as dietary habits, fluid intake, and underlying health conditions can influence the likelihood of developing future stones. Proactive management, including lifestyle modifications and medical interventions, is crucial to mitigate the risk of future episodes.

Key Aspects of Post-Passage Recovery

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Pain Management | Pain typically subsides within a few days to a couple of weeks. Over-the-counter pain relievers can help manage any lingering discomfort. Consult your doctor if pain persists or worsens. |

| Hydration | Maintaining adequate hydration is vital. Drinking plenty of fluids helps flush out the urinary tract and prevents the formation of new stones. Aim for at least 8 glasses of water daily. |

| Dietary Modifications | Dietary changes may be necessary, especially if dietary factors contributed to the initial stone formation. Your doctor can provide specific recommendations, such as reducing sodium intake, limiting oxalate-rich foods (like spinach and chocolate), or increasing calcium intake. |

| Medical Monitoring | Follow-up appointments are essential to monitor kidney function, assess for any complications, and identify underlying causes of stone formation. These appointments allow your doctor to tailor preventative strategies to your specific needs. |

| Lifestyle Changes | Lifestyle modifications, such as maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and managing any underlying medical conditions, can significantly reduce the risk of recurrent kidney stones. |

Dietary Considerations: Stages Of Passing A Kidney Stone

Diet plays a significant role in kidney stone formation and prevention. Understanding the connection between specific foods and stone development is crucial for proactive management and recurrence prevention. Dietary adjustments can be highly effective in reducing the risk of future kidney stones.

Kidney stones often form when certain substances in the urine become concentrated, leading to crystal formation. Diet influences the levels of these substances, directly impacting the risk of stone development. Specific foods can increase the concentration of these compounds, making the environment more conducive to stone formation. Conversely, some foods and nutrients can help maintain a healthy urinary environment, reducing the risk of crystal formation.

Foods Contributing to Stone Formation

Dietary choices significantly impact the likelihood of kidney stone development. Certain foods contribute to an environment conducive to stone formation by increasing the concentration of stone-forming substances in the urine.

- High-Oxalate Foods: Foods rich in oxalate, such as spinach, rhubarb, beets, nuts, chocolate, and some fruits, can increase oxalate levels in the urine. High oxalate levels can promote the formation of calcium oxalate stones, the most common type.

- High-Sodium Foods: Excessive sodium intake can increase calcium excretion in the urine, potentially contributing to calcium stone formation. Processed foods, fast food, and restaurant meals often contain high amounts of sodium.

- High-Protein Foods: A high-protein diet can lead to increased calcium and uric acid excretion in the urine, potentially increasing the risk of both calcium and uric acid stones. Red meat, poultry, and fish are examples of high-protein foods.

- Sugary Drinks: Sugary drinks, such as soda and fruit juices, can contribute to dehydration, increasing the concentration of substances in the urine and increasing the risk of stone formation.

Dietary Changes for Prevention

Adopting a balanced diet tailored to kidney stone prevention can significantly reduce the risk of recurrence. Dietary changes can effectively modify the environment within the urinary tract, hindering the formation of crystals.

- Reduced Oxalate Intake: While complete elimination of oxalate-rich foods is not necessary, moderation is key. Individuals prone to calcium oxalate stones should focus on consuming oxalate-rich foods in smaller portions and spacing them throughout the day, rather than consuming large quantities at once.

- Reduced Sodium Intake: Limiting sodium intake is crucial. Reading food labels carefully and opting for low-sodium alternatives can help manage sodium intake. Focusing on fresh, whole foods can help reduce sodium consumption.

- Balanced Protein Intake: Moderation is key for protein intake. Instead of large portions of high-protein foods, it’s beneficial to consume moderate portions and incorporate more plant-based proteins.

- Adequate Hydration: Maintaining adequate hydration by drinking plenty of water throughout the day is essential. Water helps dilute substances in the urine, reducing the concentration of potential stone-forming components.

Recommended and Restricted Foods

The following table summarizes recommended and restricted foods for kidney stone prevention. This is not an exhaustive list, and individual dietary needs may vary. Consulting with a healthcare professional or registered dietitian is highly recommended for personalized dietary guidance.

| Category | Recommended Foods | Restricted Foods |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits & Vegetables | Watermelon, cantaloupe, lemons, oranges, leafy greens (except spinach, rhubarb, and beets), asparagus, and most other vegetables | Spinach, rhubarb, beets, some types of berries |

| Dairy Products | Low-fat or fat-free dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese) | Excessive intake of high-fat dairy products |

| Proteins | Lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, lentils, tofu | Processed meats, red meat (in excess) |

| Grains & Breads | Whole grains, brown rice, whole-wheat bread | Highly processed grains, white bread |

| Other | Water, low-sodium broth | Processed foods, fast food, restaurant meals, sugary drinks, high-sodium condiments |

Medical Interventions

Kidney stones, while often manageable with lifestyle changes and pain relief, sometimes require medical intervention. This section explores the various procedures available, their effectiveness, and potential side effects. Understanding these options can empower individuals to make informed decisions with their healthcare providers.

Medical interventions for kidney stones are tailored to the size, location, and composition of the stone, as well as the patient’s overall health. Different approaches target different aspects of the stone’s removal or prevention. The most appropriate intervention is often determined through a comprehensive evaluation by a nephrologist or urologist.

Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy

Ureteroscopic lithotripsy is a minimally invasive procedure where a small, flexible tube (ureteroscope) is inserted through the urethra and into the ureter. The ureteroscope allows visualization of the stone and, in many cases, allows for its fragmentation using a laser or a small basket. This procedure is generally well-tolerated and associated with a shorter recovery time compared to other surgical options.

Success rates are typically high, especially for smaller stones.

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is a more invasive procedure used for larger stones or stones that are located deep within the kidney. A small incision is made in the back, and a nephroscope is inserted to visualize and fragment the stone. The procedure may involve the removal of the stone in pieces or in its entirety. While PCNL offers a higher success rate for larger stones, it does have a longer recovery period and a slightly higher risk of complications.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL)

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) uses shock waves to break down larger stones into smaller fragments. These fragments are then passed naturally through the urinary tract. ESWL is a non-invasive procedure, meaning no incisions are needed. It’s a good option for certain types of stones and is often a first-line treatment for some cases. However, ESWL may not be suitable for all patients, and the stone’s location and composition can affect its effectiveness.

Open Surgery

Open surgery for kidney stones is rarely necessary, reserved for complex cases where other methods are not feasible. A large incision is made to directly access and remove the stone. This method carries a higher risk of complications, longer recovery time, and more significant scarring compared to less invasive approaches. The increased invasiveness is typically balanced against the need for complete removal of large or complicated stones.

Comparative Analysis of Procedures

| Procedure | Effectiveness | Recovery Time | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy | Generally high, especially for smaller stones | Short | Infection, bleeding, injury to surrounding tissues |

| Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy | High, particularly for large or complex stones | Moderate to Long | Infection, bleeding, blood clots, kidney damage |

| Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy | Variable, depends on stone characteristics | Short to Moderate | Infection, bruising, pain, incomplete stone removal |

| Open Surgery | High, but rarely needed | Long | Significant bleeding, infection, longer recovery time, significant scarring |

Potential Side Effects of Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for kidney stones, while often effective, can carry potential side effects. These complications can vary in severity and frequency depending on the chosen procedure and individual patient factors. It is essential to discuss these potential risks with your healthcare provider to make an informed decision. Pain, infection, bleeding, and complications related to anesthesia are potential side effects.

Imaging Techniques

Pinpointing the location, size, and type of kidney stone is crucial for effective treatment planning. Various imaging techniques provide detailed information about the stone, enabling healthcare professionals to determine the best course of action. These methods are vital in assessing the stone’s characteristics and guiding interventions.

X-ray

X-rays are a fundamental imaging technique for detecting kidney stones. They are widely accessible and relatively inexpensive. X-rays are particularly effective at identifying stones composed of calcium, which appear as radiopaque shadows on the images.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

CT scans offer a more detailed view of the urinary tract and surrounding structures compared to plain X-rays. This detailed imaging allows for the precise localization of the stone and assessment of potential complications. CT scans are particularly valuable for identifying stones that are not visible on X-rays, such as those composed of uric acid or cysteine. Moreover, CT scans can reveal any associated inflammation or obstruction of the urinary tract.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound imaging uses sound waves to create images of the internal structures of the body. This technique is particularly helpful for patients with suspected kidney stones who may have contraindications to ionizing radiation, such as pregnant women. Ultrasound can provide information about the stone’s size, shape, and location, and can differentiate between stones and other abnormalities. It’s also a real-time imaging technique, allowing for dynamic assessment of the urinary tract.

Intravenous Urography (IVU)

Intravenous urography, also known as excretory urography, involves injecting a contrast dye into a vein. The dye highlights the structures of the urinary tract as it passes through the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. IVU can detect kidney stones, blockages, or other abnormalities in the urinary system. However, IVU has limitations due to the need for contrast dye and potential allergic reactions.

Comparison of Imaging Techniques

| Imaging Technique | Strengths | Limitations | Stone Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | Fast, inexpensive, widely available, good for calcium stones | Less detailed than CT, may miss smaller or non-calcium stones | Location, approximate size, shape, and composition (calcium) |

| CT Scan | Highly detailed images, detects various stone types, identifies associated abnormalities | Exposure to ionizing radiation, may require contrast dye | Precise location, size, shape, composition (calcium, uric acid, etc.), and potential complications |

| Ultrasound | Non-invasive, no ionizing radiation, real-time imaging, good for pregnant women | Lower resolution compared to CT, may not be as effective in detecting all types of stones | Location, size, shape, and composition (may be less precise than CT) |

| IVU | Provides detailed visualization of the urinary tract | Requires contrast dye, potential allergic reactions, less common now due to CT availability | Detailed visualization of the urinary tract, detection of blockages, and stones |

Closing Notes

Navigating the stages of passing a kidney stone requires a multi-faceted approach, encompassing both understanding the physical experience and implementing appropriate medical and dietary strategies. By familiarizing yourself with the symptoms, progression, and available treatments, you can better manage the discomfort and increase your chances of a smooth recovery. Remember, this guide provides general information and does not substitute professional medical advice.

Always consult with a healthcare provider for accurate diagnosis and treatment.